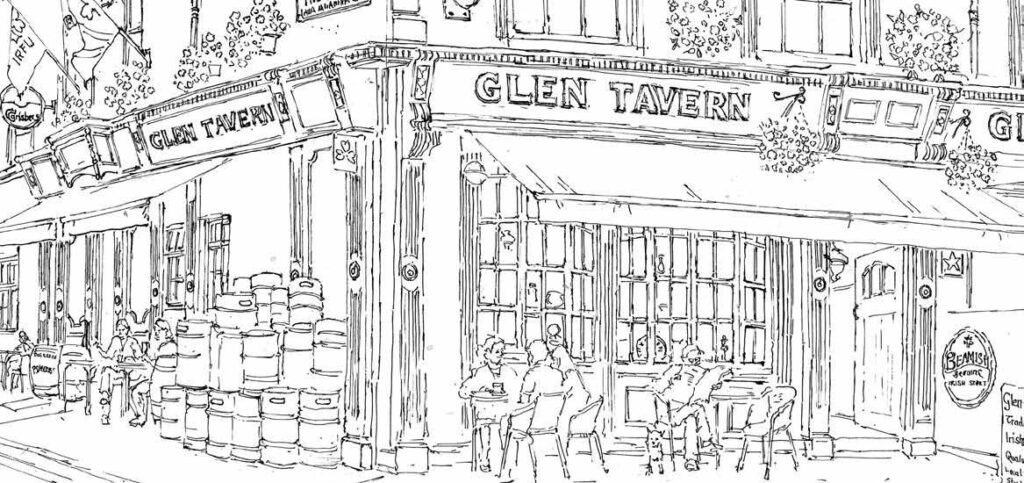

The Glen Tavern A Story Across the Centuries

By Rachael Kealy, Wordsmiths.ie

A New City

The story of the Glen Tavern begins with Edmund (or Edmond) Sexton Pery, 1st Viscount Pery (8 April 1719 – 24 February 1806). He was a member of the Anglo-Irish Ascendancy and an industrious man – not only was he a wealthy landowner, he was also barrister, a Member (and Speaker) of Parliament and something of a Georgian property developer.

When he retired, he was granted an annual pension of £3,000 – at a time in which the average labourer earned about £15 a year – and set about transforming the medieval city of Limerick into a modern metropolis.

Having already built John’s Square in the 1750s, Pery turned to South Prior’s Land, outside of the city walls (and, crucially, the Corporation’s tax boundaries). The area was known to have been largely dominated by religious orders; both the Dominican and Franciscan orders are said to have founded monasteries in the area in the 13th century.

Lord Viscount Pery worked with an Irish engineer Christopher Colles and an Italian engineer, Davis (or Daniel) Ducart, designer of the Custom House, to lay out his new neighbourhood in a modern grid pattern. He sold the land in lots to private developers, who were usually wealthy merchants. For example, the Arthur family were largely responsible for the first streets to be built in the 1770s and 1780s: Bank Place, Rutland Street and Patrick Street.

Glentworth Street, Mallow Street and Cecil Street came later and were named after Lord Viscount Pery’s brother, William Cecil Pery, later Bishop of Limerick and Lord Glentworth of Mallow.

Over the following decades, the new streets were filled with elegant three-bay

four-storey-over-basement residences. A travel writer by the name of Arthur Young visited the city in 1776 and commented on Newtown Pery: ‘The houses are new ones, of brick, large and in right lines…here are docks, quays, and a custom-house…this part of Limerick is very chearful (sic) and agreeable, and carries all the marks of a flourishing place’.[1]

The original lease of the development land containing Lower Glentworth Street appears to have been between Edmond Lord Viscount Pery and William Marrett, dated 31st October 1800. A fee-farm grant was then made between William Henry Tennison, Earl of Limerick (Viscount Edmund Pery’s grandson) and Joseph Fogerty on 7th September 1838.[ii]

Mr Fogerty (1806 – 1887) was a widely-known Limerick-based builder and architect, and is possibly responsible for the construction of the buildings which now make up the Glen Tavern. He was also a fan of the arts, first erecting a circus on Queen Street (now Davis Street), and later establishing the hugely-popular Theatre Royal on Henry Street.

A Distinguished Family Home

Newtown Pery quickly became the most fashionable address in the city, with homes owned by members of the clergy, the military and professional classes. One such family was the Rydings (sometimes listed as Ridings), who practiced as dentists and lived in 1 Lower Glentworth Street from the 1850s[iii]. They would have made much use of the Theatre Royal (which gave the name to Theatre Lane alongside their house, on which Freddy’s Bistro is now situated) and Roche’s Hanging Gardens, a botanical wonderland, which was just around the corner.

They were an industrious family, with relatives operating from a Mallow Street address as well. In 1883, Dr Henry Stephen Ryding won an honourable mention in the Cork Industrial Exhibition for his well-designed dentist’s chair, which was described as ‘a strong, useful chair, well adapted for country practice’ although the judging panel also noted it cannot ‘compete with the newer and more expensive kinds of American chairs’.[iv]

Nathanial Stephenson Ryding died in 1864 and the next Dr Ryding (believed to be Frederick) passed in 1892, at which time the property ended its tenure as a family home.

Limerick’s First Free Public Library

Since 1889, when the Library Acts were adopted by the Limerick Corporation, there had been a great deal of activity concerning the establishment of a free library. Committees, meetings and focus groups were set up, leading to endless discussion – sometimes heated – about how, when and where to create a free, public library.

In 1892 the Committee identified 1 Glentworth Street as suitable location, entering into a lease for £30 a year. A sub-committee then set about refurbishing the building and finding a suitable librarian to staff it. The latter task proved quite arduous: the interviewers were taken aback by ‘the utter and total ignorance of the men who came before them. They could scarcely believe it possible that in a city like Limerick, respectable intelligent-looking men such as the applicants could be so thoroughly unacquainted with literature.’ Few of them had any idea where the celebrated author Gerald Griffin was born (it was Limerick) and some had never even heard of the literary superstar Lord Byron.[v]

Eventually, after much to-ing and fro-ing, they found the right man: Mr John Hogan. Just past fifty at the time of his appointment, Mr Hogan had led a busy life as a member of the Bakers’ Guild, a trade union official, and a secretary of Limerick Congregated Trades. He also maintained a strong interest in literature and the arts – he was said to be a close friend of the self-styled ‘Bard of Thomond’, Michael Hogan.

Finding the right location was one thing, but filling it with books was quite another. Luckily, the Committee already had in their possession an impressive collection of volumes donated to them some years earlier by Mr George Geary Bennis, a wealthy Paris-based publisher who was born in Limerick in 1793. Although he had achieved great financial success abroad, he never forgot his home city, bequeathing his large private collection of books in English, French, Spanish and Italian to Limerick Corporation ‘for the free use of the

citizens’. After his death in 1866, his books were collected in France by his nephew and returned to Limerick, where the precious collection was shunted from one storeroom to another for years, offering nothing to the public except ever-increasing dust.

The previously-mentioned poet Michael Hogan lampooned the Limerick Corporation for their shameful lack of care of this treasure, writing: ‘A library was sent of late / Bequeathed by a dying man / To the erudite Corporation clan / Poor man, he really did resign / His literary pearls to swine.’

The books eventually made their way into the public’s hands at 1 Glentworth Street, finally fulfilling a dying man’s wish some 27 years after his passing. Over time, more volumes were added, filling nine rooms across three floors. The vast majority of visitors were there to peruse periodicals or newspapers and most people preferred to read in the building itself than borrow books overnight. This may be attributed to the quality and comfort of 1 Glentworth Street compared to the alternative – their homes.

In 1898 the Limerick Chronicle detailed the annual report of the Corporation committee: there were, at that stage, more than 1,000 members, some 291 daily visitors, and over 70 books loaned to ‘home-readers’ every day. That year, the shelves groaned with more than 4,300 books, with history and fiction the most popular choice.

788 books had been purchased at a cost of £150 (carefully selected to guard against ‘objectionable literature’). This meant that each book cost about 4 shillings, give or take. A working man back then earned around 20 shillings a week, a female shop assistant as little as 7[vi]. The free public library offered a vital resource to the hard-working people of Limerick, for whom the simple act of reading a book was a luxury very few could afford.

The Chronicle deems the library a highly successful venture, but already showing signs of outgrowing its location: ‘ladies are practically excluded, there being no place where they might sit apart to read newspapers or periodicals’. It appears they weren’t excluded quite enough for one correspondent with the newspaper, who wrote crossly of having to wait while the lady members’ ‘insatiable appetite for the sensational’ was sated before his ‘legitimate literary-inclined’ needs could be met.[vii]

In the 1901 census, the population of Limerick city was booming, at some 38,000 citizens. John Hogan (58) and his wife Mary (48) were still living at the address, and serving as librarians. The couple did not have any children, and appear to have fully devoted themselves to the task at hand, with opening hours running up to nine o’clock at night.

That same year, John passed away in St. John’s Hospital. In a rare move back then, the Committee voted for Mary to continue in her husband’s stead, with an assistant librarian.

However, her tenure was to be short, because in October of 1903, the foundation stone of a new library was laid by the billionaire Scottish-American philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. The building, which still stands at the corner of People’s Park, is now the Limerick CityGallery of Art. Mary Hogan served as deputy librarian to the director of the new library until her death in 1923.

A Century of Provisions and Pints

There is a brief reference to 1 Lower Glentworth Street becoming home to the Mechanics Institute in 1908 [viii], but by 1911 it had been transformed into a public house, run by Mr James O’Donovan, who lived there with an assistant.

Elsewhere on the premises (likely overhead) lived a young widow Mary Fitzmaurice, with her two stone cutter brothers and her four children.[ix]

Originally from Shanagolden, Co. Limerick, James was a resourceful entrepreneur. In those strict, moralistic times, many pub owners sought to soften their image by listing their premises as a spirit merchants, an importer of spirits, a grocers, or, in Jim’s case, as ‘J.O’Donovan, Oyster Saloon’.[x] Oysters were very popular at the time, as the ‘first real ‘fastfood’ for the masses of the industrial revolution.’ [xi] They also made ideal companions to a pint of high quality stout, as indeed is still the case today.

When oyster saloons fell out of fashion, he still aimed high, later listing the business as ‘J.O’Donovan, high class liquors, Lower Glentworth St’ in a 1925 trade directory.

By the time of his death in 1943, he was living at Number 5 in nearby Crescent Villas. He was remembered as an ‘ardent and consistent nationalist of the old school’ and one of the Directors of the Limerick Race Company. He is buried in Mount St. Lawrence.[xii]

The pub then passed into the hands of William (Bill) O’Donovan, who may have been a relation, as they shared a surname. After many decades running it as a successful and much-liked pub, he and his family passed the mantle to Mick McCarthy, a builder by trade.

It was later taken over by Dick Keane, before the Callanan family bought it in 1998.

Author’s Note

While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy in the above, errors can sometimes occur. The story of the Glen Tavern will always be a work in progress, and changes may be made in the future, should new information or historical sources emerge.

Further Reading

[i] Kelly, Cornelius, Ed, The Grand Tour of Limerick, pg. 61

[ii] The 1907 ‘Sale of Limerick’ Catalogue, accessed 16th March 2019

[iii] Limerick City Trades Register, accessed 16th March 2019

[iv] Cork Industrial Exhibition Report of Executive Committee, Awards of Jurors, and Statement of Accounts, 1883, accessed 16th March 2019

[v] Lane, Leeann and Murphy, William, Eds., Leisure and the Irish in the Nineteenth Century, pg 108

[vi] ‘The World of Work’, Dublin City Public Library, accessed 16th March 2019

[vii] The Limerick Chronicle, August 30th, 1898, accessed 16th March 2019

[viii] General Valuation of Ireland, pg. 15, accessed 17th March 2019

[ix] Irish Census 1911, accessed 17th March 2019

[x] Limerick City Trades Register, accessed 16th March 2019

[xi] Mac Con Iomaire, Mairtin The History of Seafood in Irish Cuisine and Culture, accessed 17th March 2019

[xii] The Limerick Chronicle, September 10th, 1943, accessed 16th March 2019